Dora, Alabama – The Place That We Call Home -Dora has an interesting history. A place settled by people who were not afraid of work. People who scraped out a life for their families working long hours for little pay breathing dust from the black gold that has been both a blessing and a curse for the people here.

Nat Self is the author of a book “Echoes of the Great Depression” which is about Dora and the surrounding area. What’s more amazing to me is that he is donating proceeds from the sale of the first 800 books to local charities.

Nat has graciously agreed to contribute stories for our community website and I am excited to bring you the first of a series of stories that will give you some insight to the humble beginnings of The Place That We Call Home.

Rick

More about the book and Nat Self can be found on his website: http://www.natself.net/

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND by Nat Self

Prior to the Civil War coal had already become an inexpensive fuel that caused substantial changes in the marketplace and lifestyle of all industrial nations. Coal generated the energy that moved powerful steamships, locomotives, and industrial equipment, and it heated many homes and businesses. Although the value of coal greatly increased during the Civil War, no one in their wildest dreams visualized the contributions it would make as a driving force of the industrial revolution during the ensuing years.

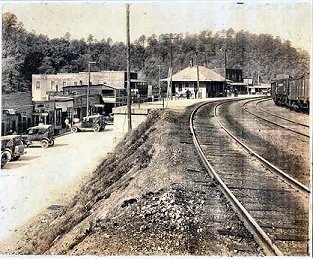

Shortly after the Civil War, many large and small coal prospectors, especially in Jefferson and Walker Counties in Alabama, explored the nearby mountains and hollows for accessible veins of coal. Several prospectors discovered numerous seams in the Horse Creek area in eastern Walker County, but there were no viable means for transporting the coal to market.Shortly after the Kansas City, Memphis, and Birmingham Railroad line was completed through the Horse Creek settlement in 1886, railroad officials named the newly built depot Sharon. When coal operators in Jefferson County whiffed the fresh coal dust riding the eastward breeze, they hurriedly formed mergers, pooled resources, and with high-pitched excitement rushed to the coalfields of Horse Creek near Sharon so they could become rich mining what was commonly known as “black diamond.”

A flurry of coal-mining activity ensued. Railroad tracks were extended around mountains and up hollows where coal-processing tipples, washers, and loading bins were rapidly constructed. One-horse-wagon mines, pick-and-shovel push-mines, and modern-equipped mines financed by large coal companies began extracting vast quantities of coal from the Horse Creek region. Owners of a new mine assigned a number to them. Usually the owners of a productive mine constructed rental houses nearby for their workers and assigned the number of the mine to the mining camp.

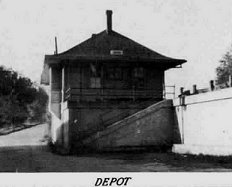

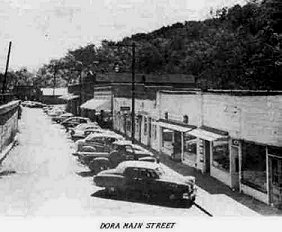

The business area of Sharon developed on the southwest hillside parallel to the railroad tracks. Stores were built on the side of Main Street facing the concrete bulkhead, ranging in height up to twenty feet that supported the railroad tracks and depot. Stubborn businessmen unhesitatingly invested their resources in what—except for the magnetic fascination of the railroad depot—was one of the most unlikely business locations. Even so, the business section rapidly grew as a sidesaddle to the depot and railroad tracks

In 1897 Sharon was incorporated as the town of Horse Creek. In 1906 the name of the town again was changed, this time to Dora. Yet many of us who later grew up in and around Dora established sentimental roots nurtured and strengthened by nostalgia of “Horse Creek.”

By 1910 Dora had grown to include over a dozen general merchandise stores, a soft-drink bottling company, lumberyard, meat market, livery stable, and furniture, contracting, and undertaking firms. The town also included two hotels, a restaurant, and the Dora Banking and Trust Company. Three physicians, a dentist, a lawyer, and two justices of the peace served the population of about 800 people. Between 1920 and 1930 Dora grew to include an automobile agency and a movie theater.

During the early1920s Kershaw, which was named after two brothers who pioneered coal mining in the area, became a thriving coal-mining camp. Located about two and one-half miles northwest of Dora, Kershaw had easily accessible veins of coal that attracted investors as well as energetic farmers, including my father, Sebern Lee Self, a recently discharged doughboy.

World War I had drawn many young men from farm families to serve their country, and in early December 1917, and after helping his family gather the crops, my father had volunteered for the U.S. Army. Twenty-one months later he received an honorable discharge. With the glitter of the bright lights of many cities in France and Germany as well as New York City fresh on his mind, my father like many other farm boys could not remain on the farm.

The popular tune of the times “How Do You Keep Them Down on the Farm?” raised an appropriate question that was promptly answered by most former doughboy farmers marching to work at industrial plants, coal mines, construction, and other non-farming endeavors.

Dad headed for the coal mine of Mulga in Jefferson County for several months before going to Kershaw in 1921. He boarded with the Carl Yarborough family and met a younger sister of Mrs. Yarborough named Gladys Roberts. On May 22, 1922, twenty-seven-year-old Sebern L. Self and eighteen-year-old Gladys Roberts married and moved into a three-room shotgun house in Kershaw Mining Camp.

Dad arranged to lease a coal-cutting machine from the company to cut seams of coal during the night. The electric coal-cutting machine resembled a giant chain saw. It was equipped with a seven to eight-foot-long steel bar with a revolving chain studded with bits. The machine ripped a cut several feet deep at the bottom of the coal seam, leaving a smooth flat floor after the coal was removed. Coal drillers and shooters followed the cutting machine and drilled holes four to five feet deep several inches apart in the face of the coal seam. They poked sticks of dynamite attached to long fuses into the holes and then tamped in coal fines. The length of each fuse and the order in which they were lit determined the timing of each dynamite blast.

By daybreak each workday the blasting powder smoke and coal dust had settled sufficiently in the poorly ventilated mine so that coal loaders armed with hand shovels could load the coal into squatty, wide mining cars, set roof support timbers, and extend the steel tracks. Each coal loader hung a small metal disk with his identification number onto the side of his loaded cars. An electric motor operator pulled the loaded cars to the surface of the mine, where workers at the tipple removed the metal identification disks from the cars so the appropriate loaders could be credited.

The company paid Dad, who operated the coal-cutting machine for all the tons of coal mined. Dad worked long hours five or six nights a week, and his earnings exceeded those of the mining superintendent. Most coal miners spent their hard-earned money freely. Dad bought a new automobile every odd year during the 1920s.

By the end of 1927 my parents had four children: two girls followed by two boys born fifteen to nineteen months apart. My parents moved from the three-room shotgun house to a nearby four-room house and furnished it with fine furniture, a hand-cranked phonograph, and an electric radio. They bought expensive clothes and quality food. Dad bought an English bulldog puppy, had his ears trimmed, his tail bobbed, and named him Bulger. To round out the status symbol of owning a thoroughbred bulldog, Dad dressed Bulger in a fancy black-leather harness and a collar embedded with shiny brass ornaments.

Many coal miners who grew up poor on the farm with little formal education were now making more money than they had ever dreamed possible. For them these were the days of sunshine, milk, and honey. On payday, usually every other Saturday, most coal miners bought light bread, bologna, ham, steak, bags of candy, and other special treats for the “ol’ lady” and kids. More than a few of the miners bought several cigars and a bottle of bootleg whiskey. Many of them didn’t drink booze, fight cocks, or gamble, but all of them were rough, tough as a seasoned hickory pick handle, hardworking, and willing to labor in a hazardous environment. Few, if any, failed to award themselves in some manner when they were paid for their labors.

Most owners of large coalmines in Dora and the surrounding area issued temporary currency called “scrip” or “clacker.” This company-issued currency could be used as legal tender at company-owned commissaries and could be discounted at several privately owned stores. A few opportunists bought clacker from miners by paying 80¢ in U.S. currency for $1 in clacker. The opportunists, usually coal miners, spent the clacker at the company store buying only limited goods that cost the same as sold by town merchants.

Large coal companies also issued their own currency to their workers who needed to buy goods between paydays. They issued scrip, temporary paper currency (books of tear-out coupons), or clacker, temporary metal currency, to miners at their request and encumbered against their earnings. Clacker became more popular in this area and remained in use for many years.

By 1929 many coalmines had flourished for several years in the Dora area with a large number of them closed for various reasons, including long underground expensive haulage, excessive slate, rock, methane gas, and groundwater. It was not uncommon for a coal company to close one mine and then open two new ones.

Kershaw became a coal-mining hotbed during the 1920s. Several coal-mining companies, including the Kershaw Mining Company and Pratt Fuel

Company, developed the Kershaw community from 1919 to the early 1930s. Practically all the houses in this settlement, which were built and owned by the coal-mining companies and rented to miners, were standard three-room shotgun houses or four-room box houses.

A typical company-owned house was a wood-frame structure supported by wood pillars resting on thick flat rocks with horizontal dark-brown creosoted clapboards on the outside. A few larger company houses built on No. 10 Hill and painted white were rented to company officials. All of the company-owned houses included front porches that served as gathering places for family and neighbors.

Since the coal-company in Kershaw generated its own electricity, most of the houses were wired with electrical lines.

Each room had a single drop-cord dangling from the center of the ceiling with a light-bulb socket and switch attached to the end of the cord. Most company-owned houses had two brick chimneys—one a flue to a brick hearth with an iron grate and framed with a wooden mantelpiece in a front room, the other was a flue for the cooking stove in a back room kitchen.

Shopping in Style

In spite of the bad economic news, Dad was still working on a regular basis. On a beautiful sunny autumn payday, Mom told us that we were going shopping and then we were going to the moving picture show in Dora. She washed and dressed us in our best clothes, and she and Dad washed up and dressed in their finest clothing and polished shoes.

Mom’s makeup and perfume had a pleasant fragrance, while Dad’s shaving lotion smelled fresh and clean. Soon we were inside the Whippet and headed toward Dora with the sun sinking in the west and a dark cloud visible in front of us to the east. Dad drove about three miles past Dora to G. May’s clothing store at old Dora junction near Sumiton, where my parents had shopped for many years. After Mom finished her shopping, we traveled back to Dora, and Dad parked the car in front of Palmer Mercantile Company.

The Moving-Picture Show

After buying groceries, we walked a short way down a crowded sidewalk to the moving-picture show. Many people were in line buying theater tickets, and they were in a jovial mood, talking, and laughing. Most men in the crowd were smoking cigars. Practically all of the people in town were neighbors, friends, or acquaintances. This was a big event, especially for the families of coal miners who had been paid today.

After Dad bought the tickets, we walked and pushed with a crowd of people into the lobby of the theater, where I breathed the aroma of fresh popcorn. Dad bought several bags of popcorn, and then we moved with the crowd into the lighted theater, which had a floor that sloped toward the large white screen at the lower end of the room. Black people sat in the balcony suspended over about a third of the main floor. We found seats in a side section near the rear. Soon the lights were turned out, and everything turned pitch black before the moving-picture show began.

After eating most of my popcorn, I fell asleep. The next thing that I knew, Dad was shaking my shoulder. I had slept through the entire show, and the lights were on. We moved slowly in the crowd of people leaving the theater, and I couldn’t see where we were going with all those tall people in front of me. Finally we reached the lobby. I heard someone yell, “Look, it’s a-rainin’!”

We walked out of the theater and onto the wet street where a misty rain fell. Stepping fast we rushed to our car and scrambled into it while Dad hurried back into Palmer’s store to buy our breakfast beefsteak.

When Dad returned to the car, he headed it toward home in Kershaw. The pavement of Main Street ended before we started down the steep hill a short distance past the railroad depot. From my place in the middle of the rear seat I watched the steady oscillation of the wipers sweeping the windshield as Dad drove down the steep slippery road past the little calaboose and toward the tunnel. Inside the tunnel the engine noise drowned out the flapping sound of the windshield wipers.

The steady rain peppered down. I curled up on the seat. Listening to the rhythm of the windshield wipers, hum of the engine, and vibrations of the car, I fell asleep again.

Grandpa’s Death

Several days before Christmas 1929, Mom and Dad dressed to go shopping. Mom wore a beautiful dark-blue dress, black, high-top, patent leather shoes, a full-length dark coat with a fox fur-trimmed collar, and black leather gloves. Her gray-green eyes, set back and above her high cheekbones, sparkled as she pushed back her long black wavy hair. Expensive makeup enhanced her clear-beige complexion. Dad wore his blue serge wool suit, white starched shirt, a red silk tie, polished black shoes, and a dark-gray, felt Stetson hat.

Our good neighbor, Mrs. Friday, came over to our house to baby-sit while our parents were away selecting our Christmas gifts. We sat near the warm fireplace singing Christmas carols and listening to Christmas stories Mrs. Friday told us.

After a long while, Mom and Dad returned, and they did not disappoint us . They brought a box of apples, a crate of oranges, a large bag of mixed nuts, and a bag of candy. Unknown to us, they had stored our presents in the garage.

A few days later, Grandpa Self came on the train to visit us. He had sold his cotton crop and had come to pay back a loan Dad had made to him during the spring for financing cottonseed and fertilizer. He brought each of us children a Christmas gift. Sitting in a large cane rocking chair in front of the warm fireplace, he pulled me onto his lap and gave me a glass pistol filled with small colored candy balls.

Later that evening he told Mom that he felt very tired and needed to retire to bed for the night.

Mom said that Grandpa was running a high fever. Dad went after Dr. Luther Terry, our local doctor, who brought his black leather bag with him. He spent a lot of time in the closed front room diagnosing and medicating Grandpa. Finally, he opened the door and told my parents that Grandpa was very ill with double pneumonia. Dad and Mom took turns tending Grandpa throughout the rest of the night. The next day Mom wanted quiet in the house, so she put coats and caps on my two sisters and me and sent us outside to play. The sun was bright, but it was extremely cold and the ground was frozen. I discovered that ice had formed underneath a thin layer of frozen soil, and I entertained myself by crushing the crunchy ice by stepping on it. Bulger, always nearby, played with us, but he wouldn’t eat the ice I tried to feed him.

Grandpa’s condition deteriorated rapidly, and on December 20, 1929, the silent, absolute, relentless phantom of death moved in and transformed his life. That was the first time I had seen my parents dispirited with a heavy heart. Their sadness greatly concerned and confused me. Mom explained that Grandpa had gone to a much better place in heaven where he would remain forever.

Dad drove to Uncle Lothie Tesseneer’s house in the Haleyville area and informed his sister, Aunt Nellie, while sending word to the other family members that Grandpa had died. He brought Aunt Nellie home with him and other family members came later on the train.

The wind became extremely frigid, and dark clouds covered the sky. Late afternoon on December 21, snow began falling on already frozen ground. Neighbors brought platters and dishes of food to our house, and we gathered by our warm fireplace in the front room. Some of the adults sat in chairs in front of the fire, while others and all of the children sat on the floor. Conversation was held to an occasional whisper. Grandpa’s body lay in a beautiful casket in the other front room, where he had died. Many adults and all of the children slept on the floor on pallets that night. Some of our kin spent the night with our neighbors. After most of us bedded down, silent snowflakes floated to the ground.

Daybreak on December 22 brought a flurry of activity. Soft voices discussed the snow as breakfast was being prepared. I scrambled to my feet, rushed to the window, rubbed condensation from it with my sleeve, and looked outside at the thick white blanket. After breakfast Mom put coats on us and let us play on the front porch. First we scooped up snow on the steps to make snowballs to eat. Then my sisters and I threw snowballs at one another.

Our Whippet, which was not in the garage because of the boxes of Christmas gifts stored there, sat in the driveway. Dad measured the depth of the snow on the car to be nearly six inches. The snow covered everything in all directions that I could see.

Dad made arrangements to have Grandpa buried in East Dora Cemetery, with the funeral scheduled at the Dora Church of God for the afternoon of December 22. Family members, neighbors, and other friends drove cars through the deep snow to gather at the church. While the services were conducted inside the church, my two sisters, brother and I were left in custody of Mrs. Friday in the Whippet, which Dad had parked in front of the church alongside the main road. I was misbehaving in the backseat when Mrs. Friday said to me, “Now I want you to roll that window up and be a good boy.”

I thought about that for a moment and then responded, “When I get home, I’m going to take my belt to you.”

I watched as the pallbearers appeared in the open door of the church carrying the coffin. They carefully walked down the snow-covered steps and waded through the snow in front of the church to a nearby flatbed truck where they placed the coffin. Slowly the truck moved up the steep snow covered hill toward the cemetery. Not halfway up the hill the rear wheels of the truck began spinning, and it could go no farther. The pallbearers, all wearing white gloves, pulled the coffin off the truck and carried it up the hill to the freshly dug grave at the edge of the cemetery. I watched my parents, Grandma, and other family members followed by a crowd of people dressed in heavy coats climb up the slippery hill to the burial site.

Night Noises

Mom could not sleep well with Dad working all night. The least noise disturbed her as she lay listening. This began early in their marriage, so Dad bought a pearl handle .38 special and taught her to use it during target practice. She kept the loaded six-shooter in a lamp table drawer near her bed at night while Dad was away.

One night all of us children were in bed asleep. Sometime during the cold night Mom, who had been awake for no telling how long, thought she heard a noise at the back of our house. With a nightlight on in the back room, she tiptoed to the back door with the pistol in hand. She shouted, “Who’s there, who is it?”

Receiving no response she turned the light out and strained her eyes looking through a window to see if she could see anyone or anything. Seeing and hearing nothing, she turned the light on and shouted again, “Who are you?”

There was no answer. Mom cocked the pistol and cracked opened the door. She neither saw nor heard anything. Pointing the pistol skyward, she squeezed the trigger two or three times. Then she locked the door and went to bed.

Well Water

During a bright spring cloudless day during 1930, Mom removed two empty water buckets from the shelf and instructed us to listen to the phonograph while she went to the well. Placing the buckets on the floor, she raised the top of the phonograph and positioned a large round, flat, black, grooved record on the felt turntable. Then she wound up the turntable spring with an attached crank and lowered the arm, placing the phonograph needle in the first groove on the record. Looking at Judy, she instructed her to turn over the record after the first side had finished playing.

The phonograph began playing “She’ll Be Coming Around the Mountain When She Comes.” I asked Mom if I could go with her, and she handed me a small bucket. We walked down the porch steps with Bulger at our side. Several older boys, who were eight, ten and twelve years old, were playing baseball on the rough ground in front of our house. One of them shouted, “Chunk it over the plate!” When the batter hit the ball, everyone started running in all directions as I stood there watching. Ed Still, the umpire tried to impress the others with a big word by shouting, “You’re auto-tomatically out!”

All of the boys started fussing, some saying that the runner wasn’t out, while others said that he was. One of them threw his glove to the ground shouting, “I quit. I ain’t a-gonna play eny more!”

I walked with Mom about 250 feet to the community well. She removed the wooden plug from the well pipe that protected the water from foreign matter, and then she lifted the slim three-foot-long well bucket from a large nail in the weathered well housing.

The bucket was secured to one end of a rope that looped up and over a pulley attached to the top of the well structure and then secured to and wound around a solid wooden horizontal barrel that had been fashioned into a windlass. While the weight of the well bucket lowered it down the pipe, rope spun off the humming wooden drum with the free-spinning metal crank becoming a blur. When the well bucket hit water, the windlass stopped, and the bucket filled with water. Mom drew enough water to fill her two buckets and mine, and then she hung the well bucket on the nail and replaced the wooden stopper in the well pipe.

House Play

Before we arrived at our front yard with the filled water buckets, I heard the phonograph playing what sounded like the “Charleston.” We walked into the front room where Judy and Orlane were trying to dance. Mom placed her two water buckets on the floor and put her hands on her hips. In her direct Spartan style she declared, “You girls stop dancing this minute. That’s the work of the ol’ bogeyman!”

“Mom,” Judy explained, “we’re practicing a play that we’re going to put on.”

“I want to play,” I whined.

“Who pulled your chain little brother?” Judy snapped. “This is a play of highfalutin’ movie stars, not games.”

Mom instructed Judy to hold her tongue while she considered whether or not to allow the dancing to continue. “Very well,” she replied. “If you’re working on a play for the family to see, I suppose it’ll be all right.”

Wanting some attention, I pleaded, “I want to hear the “Little Red Rooster.”

Judy placed the “Little Red Rooster” record on the turntable and played it for me. Then, she motioned for Orlane and me to follow her to the front porch. She whispered to us, “We’re going to put on a play and make some money.” Orlane and I sidled up closer to hear more. “I’m going to be the movie star in the play,” Judy explained.

Orlane protested, “I want to be a movie star.”

Judy responded, “No, I’m the oldest one. I’ll be the movie star.” She led us back into the front room and closed all the doors. After applying some of Mom’s makeup, she put on one of Mom’s hats and gave one to Orlane. Then she removed two pairs of Mom’s dress slippers from the chifforobe and gave one pair to Orlane. “I’m going to be behind this chifforobe,” Judy explained as she rolled one side of it away from the wall.

She took Orlane by the arm and led her to where she said was the center of the stage. “Now you stand right here and be sure to talk proper when you introduce me,” Judy instructed Orlane.

“What do I say?” questioned Orlane.

Judy responded. “You say real loud, ‘Here is the most beautiful movie star in the whole wide world, Mrs. Judy Lumbard.’ I’ll come out from behind the chifforobe, turn on the phonograph, and do a dance.”

By now I was getting concerned about my part in the play. “What do I do?” I asked.

Judy had an answer. She took one of Dad’s hats from the chifforobe and plopped it on my head. “There now, you’re the ticket seller,” she said.

“I can’t see,” I complained.

Judy crumpled up a sheet of newspaper, stuffed it in the hat, and placed it back on my head. Tearing two small pieces of paper from the edge of a newspaper she marked ten cents on one and five cents on the other one. She handed the two pieces of paper to me saying, “Here, sell these tickets to Mom. The play is going to start in a few minutes.”

Mom was busy in the kitchen when I walked in with Dad’s hat on the back of my head. She looked at me and asked, “Do I know you young fellow?”

“I’m the ticket seller for the play,” I answered.

Mom questioned, “What time does the play start?”

I gestured toward the front room and responded, “The play is ready to start. Here are two tickets for you and Melton.”

I handed the two tickets to her. She took them and read the price on each one. She washed her hands in the wash pan, gave me fifteen cents for the tickets, and told me to wake up Melton, who was asleep in the other front room.

Bulger was waiting on our front porch straining to hear a faint sound of our approaching Whippet. Practically all day a steady soft rain had been falling, and any sound of an automobile engine prompted Bulger to cock his head to one side and stare at the curve in the road beyond the community well where our car would first appear. He became so familiar with the sound of the Whippet’s motor that he ran to meet it before he saw it. Finally hearing the right sound, he bolted from the porch to the yard and down the muddy road as fast as his short legs could carry him.

When Dad saw Bulger, he stopped the car as he always did and waited for Bulger who was running lickety-split through mud holes to jump upon the running board for a ride home.

He lay there panting for breath with a pulsating pink tongue. Sparing no effort for a short ride home, he was now tired, wet, and muddy, but happy.

Dad hurried through the rain from the garage some thirty feet away to the front porch. He patted Bulger’s wet head, and Bulger licked his hand. Then, suddenly Bulger shook his body with every ounce of energy he could muster, and the vibrations sent a spray of water off his fur coat.

Dad cuddled something in his right hand near his belt buckle that looked like a small animal. Before anyone could ask what it was, he said, “This is a civet cat that’s had its odor glands removed.”

He took his hat off and hung it on a nail on the wall behind a door. We children, with big bright eyes and pounding hearts, gathered around to see our new white-and-black striped pet.

About a year ago Dad had brought home a gray fox. He had put a fancy collar and a long chain on the fox and secured it to one of the wooden house supports. Being fearful of people, the fox sought out the darkest place underneath the house. It was a beautiful half-grown animal, but it was unhappy being out of its habitat. Dad thought he could domesticate it, but that was before the fox made a meal of one of his prime game chickens. After Dad found nothing but feathers left of one of his chickens, the fox had to go. That day the shy, young fox won not only a fresh tasty meal but also its freedom. Dad loaded the fox, which had spent only a short period of time with us, in the car and transported it over Kershaw Mountain, where he set it free.

The civet cat had its teeth clamped on Dad’s pocket watch chain. Mom said that the poor little thing was so scared of us that it wouldn’t release the chain. Dad took a small splinter of wood from the firewood box, and while Mom held the little cat, he forced open its mouth and removed his watch chain. Dad let all of us rub the little pet before he put it in one of the cages that he had made from empty dynamite powder boxes. Dad had made a door with hardware cloth for each cage and had mounted all the cages on the wall about five feet above the front porch floor. We kept small wild animals in the cages. A cage near one end of the porch housed an owl, which perched motionless with closed eyes during the day. We enjoyed pestering the owl by tapping its cage and watching its eyelids open wide. In stone silence it seemed to scold us with a stare.

Another cage at the other end of the porch housed a gray squirrel that played on crossbars. Dad put the civet cat and a bowl of fresh water in a cage near the squirrel’s cage. Whenever disturbed, the little cat patted the floor of the cage with its right foot. Dad told us that the civet cat patted its foot as a warning before spraying its odor. Lucky for us, this one had no odor to spray.

Friend of Mine

One of my playmates was a redheaded five-year-old boy named Roy Lorance whose family lived across the road from the community well. One day Roy, who was about my age, came to show me his slingshot. He placed a small rock in the pocket of his slingshot, shot it across the road in front of our house, and then handed the slingshot to me. After shooting several rocks with his slingshot we sat down on our front porch steps. Roy said, “I killed a bird with this slingshot the other day.”

“What did you do with it?” I asked.

“I cleaned it and cooked it in the woods,” he replied.

“Did you eat it?” I asked him.

He paused for a moment then responded, “It didn’t get done, so I ate it raw.”

I didn’t believe him because Roy frequently fabricated stories. I pulled out my brand-new Barlow pocketknife from my pocket. “Look at my new pocketknife,” I said as I struggled to open the large blade.

“Boy, what a pretty knife!” he shouted.

I handed the knife to him, and he immediately started whittling on his slingshot handle. “This is a sharp knife. Can I borrow it?” he asked.

“No, I need my knife, and besides you might lose it,” I answered.

Roy handed the knife back to me and said, “Guess what I seen yesterdy?”

I looked at him and shook my head.

“Well, yesterdy I seen a cow with two teats growed together,” he said.

To me Roy was being Roy, telling me another one of his big stories. But before I could ask him about the unusual cow, his mother, far down the road, called for him as she walked toward our house.

Being hardheaded, Roy ignored his mother until he heard her yell, “Raweee, you better answer me boyee before I snatch you bald headed!”

Roy leaped to his feet. While running to his mother he hollered, “I’m a-comin’, I’m ‘a-comin’!”